What are Plankton?

Plankton are drifting aquatic life forms - organisms carried by currents, rather than by their own swimming strength.

They include some of the smallest organisms on Earth, such as microscopic algae and bacteria, as well as much larger creatures like jellyfish which, despite their size, still qualify as plankton because they cannot propel themselves effectively against ocean currents.

The word plankton comes from the Greek planktos, meaning “drifter” or “wanderer” - a perfect description of their lifestyle. Although some plankton are able to swim just enough to control how deep they are, or to get closer to their prey, many plankton cannot and so they move passively with the ocean’s flow.

What unites plankton is not their size, appearance, or taxonomy, but their way of living: drifting with the currents. This single trait binds together a remarkable collection of organisms that are central to aquatic ecosystems and the global climate.

What are the Different Types of Plankton?

Plankton represent an astonishing diversity of organisms. Scientists usually group them into four broad categories, each with a crucial role in the food web and in global biogeochemical cycles.

Types of Plankton:

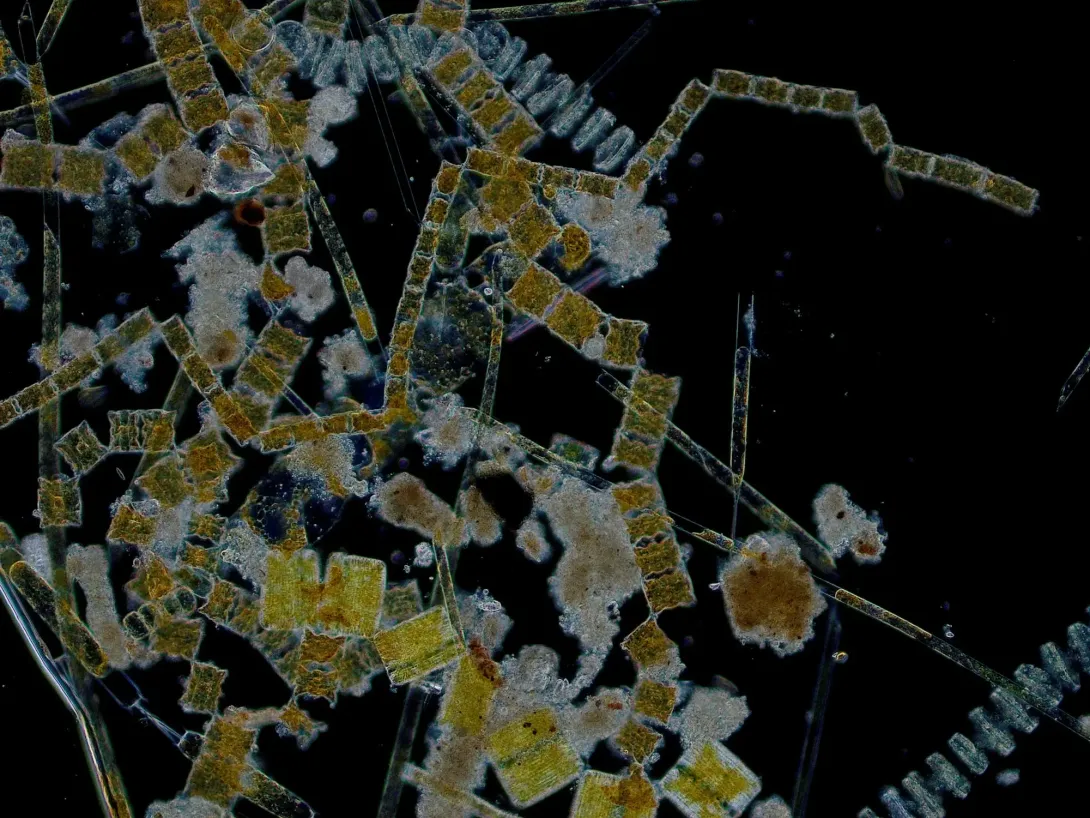

Phytoplankton are tiny, plant-like organisms that live near the ocean surface. They include algae and photosynthetic bacteria. Phytoplankton produce energy and food resources using sunlight (this is what we call photosynthesis) and form the base of aquatic food webs. Their growth depends on nutrients, light, and temperature. Their populations change with the environment, affecting marine food webs.

Image: Ditylum.

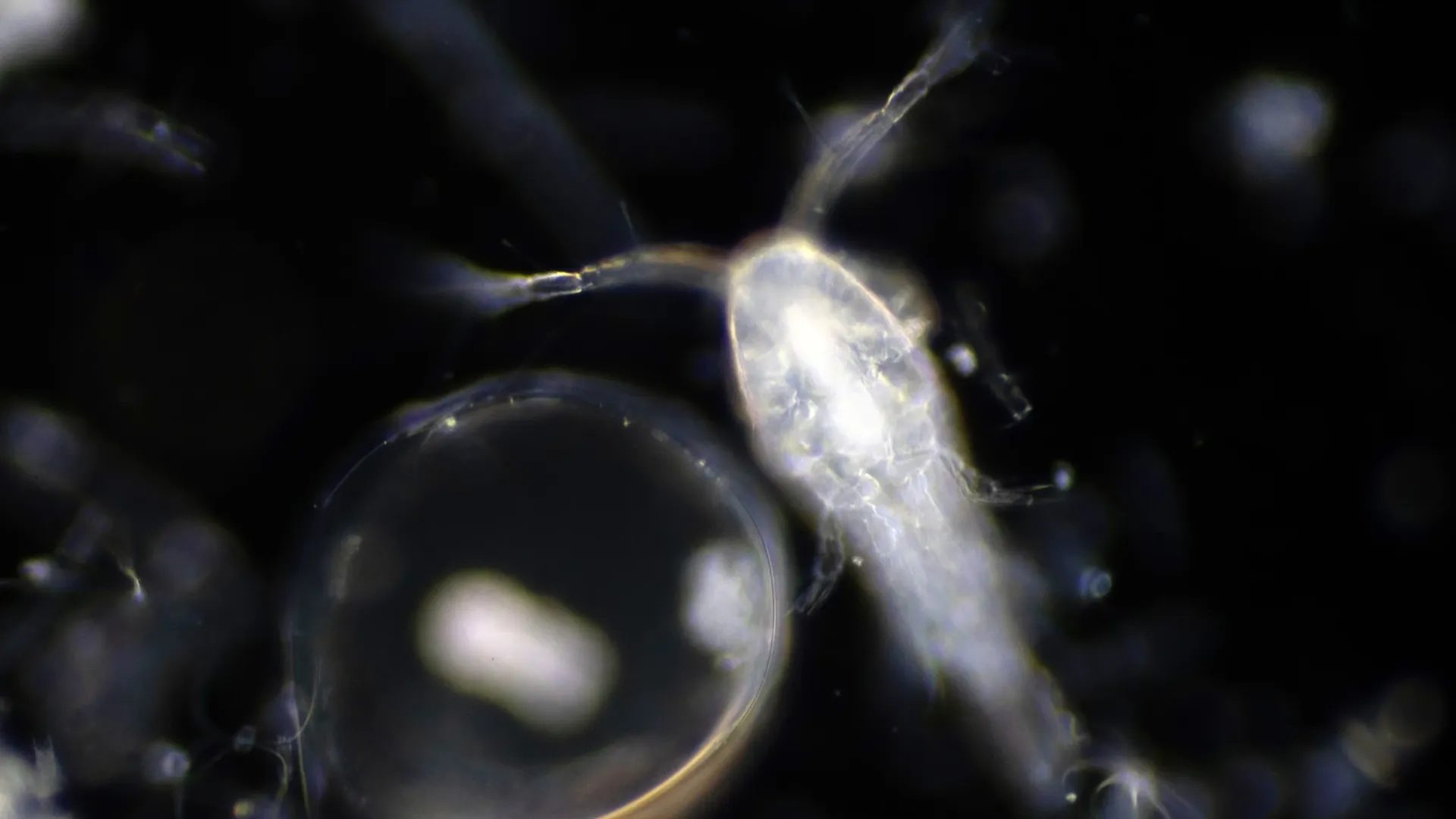

Zooplankton are animal plankton that eat phytoplankton or smaller zooplankton, and include species such as copepods, krill, jellyfish, and fish larvae. Their populations change with the environment, affecting marine food webs. They help transfer energy up the food chain and cycle nutrients through their feeding and waste.

Image: Copepod.

Bacterioplankton are the bacteria present in the water column. They are important as they recycle nutrients by breaking down organic matter. They are central to decomposition processes and nutrient regeneration, providing the phytoplankton with the nutrients needed to help sustain the productivity of aquatic ecosystems.

Image: Microscopic image of stained marine Bacterioplankton in blue.

Mycoplankton are marine fungi. Unlike phytoplankton, mycoplankton cannot photosynthesise and so get their energy from decomposing organic material, contributing to nutrient turnover.

Image: Detonula, a type of Phytoplankton. Mycoplankton are parasitic and are associated with particles and Phytoplankton.

Where are Plankton Found?

Plankton inhabit almost every aquatic environment on Earth; from freshwater lakes and rivers to estuaries, shallow coastal waters, and the open ocean. They even appear in temporary ponds and pools.

The world's oceans are the primary habitat for plankton, supporting vast and diverse communities. In the sea, phytoplankton are most concentrated in the surface layer, where sunlight penetrates and photosynthesis can take place. This sunlit zone is where phytoplankton thrive and where marine food webs begin (NOAA).

But plankton are not confined to the surface. Many zooplankton species migrate vertically through the water column in a daily rhythm known as ‘diel vertical migration’. At night, vast numbers of zooplankton rise to surface waters to feed on phytoplankton. By day, they sink into darker, deep waters to avoid predators. This daily migration is the largest migration on Earth by biomass and plays a crucial role in moving carbon and nutrients between ocean layers.

How Old are Plankton?

Plankton are ancient. Fossil evidence shows that cyanobacteria - the first phytoplankton organisms - date back approximately 2.5 billion years.

Their activity helped shape Earth’s atmosphere, as they were the first oxygen producers, paving the way for complex life.

How Big are Plankton?

Plankton size varies enormously. Many are microscopic - often numbering in the hundreds of thousands per litre of seawater - while others are visible with the naked eye.

Jellyfish, for example, can grow to enormous sizes. Larger crustaceans such as krill also form swarms that are so large they change the colour of the water. And when phytoplankton populations bloom in huge numbers, they can colour the water green, milky white, red, or brown, which is visible even from space (PML).

- Picoplankton – less than 2 micrometres wide, smaller than a red blood cell.

- Nanoplankton: from 2 to 20 micrometres wide.

- Microplankton – from 20 to 200 micrometres.

- Mesoplankton - less than a millimetre to 20 millimetres.

- Macroplankton - from 2 to 20 centimetres.

- Megaplankton – over 20 centimetres, with giant jellyfish the most obvious example.

[LIST MARKED AS POTENTIAL INFOGRAPHIC]

What Does Plankton Look Like?

Plankton are extraordinarily diverse in appearance. For example:

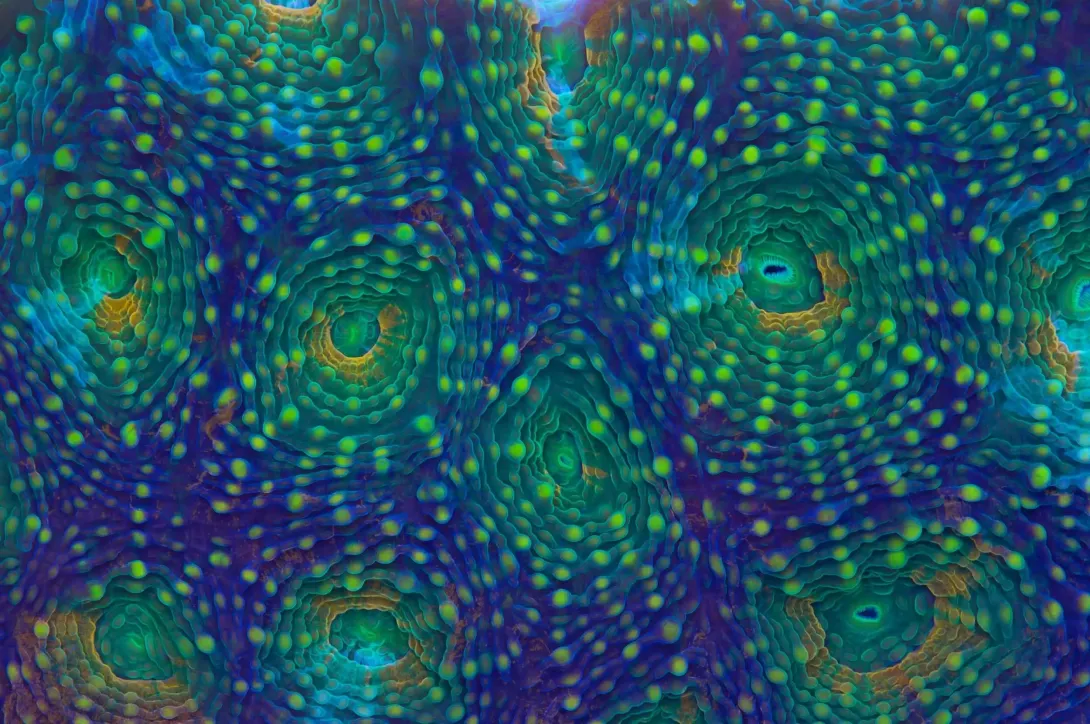

- Phytoplankton often form intricate geometric shells made of silica (diatoms) or calcium carbonate (coccolithophores). As there are many different kinds of phytoplankton, they can take all kinds of shapes and sizes.

- Zooplankton can resemble miniature shrimp, crabs, or jellyfish.

Many appear alien-like under the microscope, with delicate structures and transparent bodies.

Phytoplankton (Rhizosolenia)

Zooplankton (Euphausiacea)

What do Plankton Eat?

Plankton feeding strategies vary according to type:

- Phytoplankton – These photosynthetic organisms use sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and nutrients into organic carbon. Their growth depends on the availability of nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and iron, carbon dioxide and sunlight.

- Zooplankton – These animal plankton feed on phytoplankton and other small zooplankton, passing energy up the food web.

- Bacterioplankton and mycoplankton – These decomposers recycle nutrients by breaking down organic matter, ensuring essential elements are available to other organisms.

Plankton feeding connects the smallest drifting cells to the largest marine predators, keeping the aquatic food web turning and sustaining energy needs across ecosystems.

What Eats Plankton?

Because plankton form the base of the marine food web, a wide range of organisms depend on them:

- Zooplankton consume phytoplankton and other smaller zooplankton.

- Fish larvae and small fish feed heavily on zooplankton.

- Krill, shellfish, and sponges filter phytoplankton and organic particles from seawater.

- Other animals, including a variety of invertebrates and filter feeders, also rely on plankton as a primary food source, playing a crucial role in maintaining the balance of the food web.

- Larger predators such as seabirds, squid, and marine mammals consume zooplankton organisms.

[LIST MARKED AS POTENTIAL INFOGRAPHIC]

Do Whales Eat Plankton?

Yes. Some of the largest animals on Earth depend on plankton for survival. Baleen whales such as blue, fin and humpback whales feed mainly on krill, which are small, shrimp-like crustaceans.

Whales use baleen plates to filter seawater, capturing krill, small fish, and other planktonic organisms. This filter-feeding strategy allows them to consume vast quantities of food.

Although whales do not eat phytoplankton directly, their survival depends on the health of phytoplankton populations, which sustain krill and zooplankton. In this way, even the largest animals are tied to the drifting organisms that form the ocean’s base food source.

Do Plankton Have Different Life Cycles and How Long do They Live For?

Some plankton, known as holoplankton, remain planktonic for their entire life cycle. Copepods, diatoms, and many dinoflagellates fall into this category.

Others, called meroplankton, are planktonic only during their larval stages before developing into swimming or stationary adults. Crabs, starfish, and many fish begin life as meroplankton.

Plankton lifespans depend on the group:

Why are Plankton Important?

Plankton are not just a drifting curiosity; they are a driving force behind Earth’s climate, biodiversity and marine ecosystems worldwide. Their importance can be summarised across several key areas below.

Influence of Plankton

Discussed in more detail below, phytoplankton are responsible for about half of the oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere, making them just as critical as terrestrial plants (CPR Survey).

Nearly every marine organism relies on plankton for food, either directly or indirectly. Plankton form the foundation of the marine food chain and support the entire food web, from tiny fish larvae to whales, sustaining all levels of aquatic life (MBA).

By sustaining life from the smallest bacteria to the largest whales, plankton underpin aquatic biodiversity. Their diversity keeps ecosystems resilient, allowing them to adapt to changes in climate, pollution, and other stressors. When plankton diversity declines, ecosystems lose stability and become more vulnerable.

Phytoplankton absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide during photosynthesis, helping to regulate atmospheric CO₂ and contributing to global biogeochemical cycles. By driving photosynthesis in marine ecosystems, plankton fuel both biological and climate processes.

Many commercially valuable fish species depend on plankton at different life cycle stages. Without healthy plankton populations, fisheries and aquaculture industries would collapse.

Why is Plankton Crucial for Oxygen Production?

Phytoplankton are some of the most important oxygen producers on the planet. Like plants on land, they photosynthesise, using sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into organic carbon, while releasing oxygen.

This process occurs mainly in the sunlit layers of the ocean. The oxygen they generate supports marine life and also enters the atmosphere, providing about half of the oxygen in every breath we take.

Scientists often call phytoplankton the “lungs of the sea” because of this crucial role. Unlike forests, which are confined to land, phytoplankton cover vast areas of the ocean and respond rapidly to environmental changes. Seasonal fluctuations in their abundance can even be detected in global oxygen measurements. Without phytoplankton, Earth’s climate and breathable atmosphere would be radically different.

What is a Plankton Bloom?

A plankton bloom occurs when conditions such as sunlight and nutrients allow phytoplankton populations to grow explosively. Blooms can colour the water green, red, or brown, and can be detected from space by satellites measuring ocean colour.

Most blooms are natural and play an important role in fuelling food webs and supporting fisheries. For example, the spring bloom in the North Atlantic triggers a surge of productivity that sustains fish stocks for the year.

However, not all blooms are benign. Certain species cause harmful algal blooms (HABs), which release toxins that can kill marine life, contaminate shellfish, and affect human health. Events such as “red tides” are well-known examples.

Beyond their immediate impacts, blooms also play a role in climate regulation. When phytoplankton die, or are consumed by zooplankton whose waste then sinks, carbon is transported into deeper waters, locking it away from the atmosphere. This “biological pump” helps regulate Earth’s climate on a global scale.

How Does Climate Change Affect Plankton?

Because plankton underpin food webs and regulate the carbon cycle, these changes cascade throughout aquatic ecosystems. Impacts include shifts in fish stocks, changes in seabird and marine mammal populations, and reductions in the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide. Climate change is already altering plankton populations in ways that affect the entire ocean:

Plankton and Climate Change

Rising sea surface temperatures favour some species while disadvantaging others, reshaping community composition and influencing global patterns of plankton distribution (NIH).

Carbon dioxide dissolving into seawater lowers pH levels, threatening plankton with calcium carbonate shells such as foraminifera and coccolithophores.

Stratification, where surface waters and deeper waters no longer mix effectively, limits nutrient supply to surface phytoplankton.

Shifts in circulation patterns alter global plankton distribution.

What Happens if There is Too Much Plankton?

While plankton are essential, excessive growth can upset marine ecosystems. When nutrient pollution from agriculture or sewage fuels uncontrolled phytoplankton growth, blooms may block sunlight from reaching deeper waters, reducing photosynthesis. When these blooms die and decompose, bacteria consume large amounts of oxygen, creating hypoxic or even anoxic “dead zones” that negatively influence fish, crabs, or other marine life.

These events are not only harmful to biodiversity but also to human activities. Fisheries may collapse locally, shellfish harvesting can be suspended, and coastal communities often face economic losses. Some dead zones, such as those in the Gulf of Mexico or the Baltic Sea, now appear seasonally and span thousands of square kilometres. They show how human impacts on plankton can cascade through entire ecosystems and economies.

What Would Happen if Plankton Went Extinct?

If plankton disappeared, the consequences would be catastrophic. Without phytoplankton, the foundation of marine food webs would vanish. Zooplankton, fish larvae, and higher predators would lose their food supply, triggering a collapse of biodiversity.

At the same time, the oceans would not produce and release oxygen to the atmosphere as well as it would absorb less atmospheric carbon dioxide, so more would accumulate in the atmosphere, accelerating climate change. Quite simply, without plankton, life in the ocean and on land would not be as we know it.

How do Plankton Affect Human Health?

Phytoplankton regulate atmospheric carbon dioxide and produce oxygen, ensuring a stable climate and breathable air. Without them, human health and survival would be impossible.

Plankton also support human health directly and indirectly. Omega-3 fatty acids, derived from phytoplankton, are widely used in nutritional supplements. Certain plankton extracts are used in pharmaceuticals and skincare products.

Monitoring plankton populations is critical for safeguarding public health (MBA).

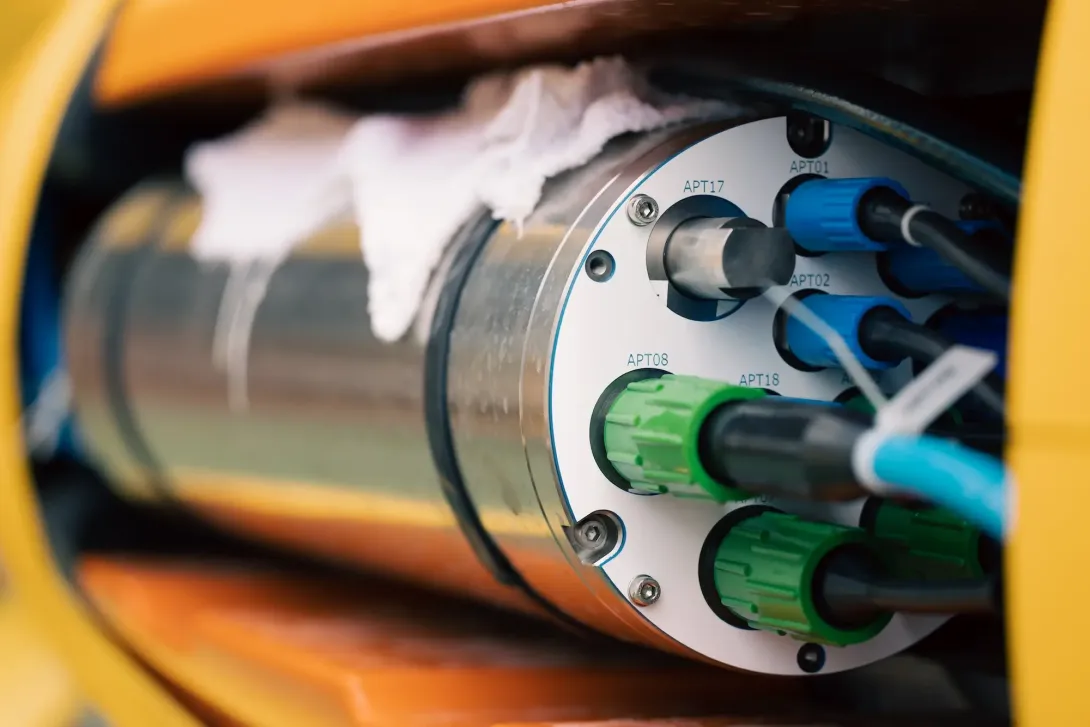

How do Scientists Study Plankton?

Studying plankton is challenging, as most are microscopic, fragile, and constantly drifting. From deep-sea expeditions to autonomous vehicles, scientists are revealing how plankton regulate nutrient cycles, oxygen production, and the global carbon cycle. Scientists therefore use a range of methods:

Plankton FAQs

Sheldon J. Plankton - the fictional character from the animated TV series SpongeBob SquarePants - is based on a copepod, a real type of animal plankton. In reality, copepods are among the most abundant animals on Earth, feeding on phytoplankton and transferring energy up the marine food web.

Plankton is a lifestyle, not a single group. The term ‘algae’ includes aquatic photosynthetic organisms, including unicellular organisms (phytoplankton) and multicellular organisms (seaweeds). Both can photosynthesise, but phytoplankton drift with the currents, whereas seaweeds are not free-floating.

Plankton are not defined by taxonomy but by behaviour. Some plankton are plant-like photosynthetic organisms, others are animal plankton, and still others are bacteria or fungi. The term “plankton” describes how they live, not what they are.

Most plankton lack complex eyes. However, many have light-sensitive spots or organelles that help them detect light and orient themselves in the water column. Some zooplankton, such as copepods, do have simple eye structures.

Reproduction varies widely, for example:

- Phytoplankton such as algae typically reproduce sexually and/or asexually, dividing rapidly to form new cells.

- Zooplankton often reproduce sexually, producing eggs and larvae that drift before maturing.

Yes. Certain plankton, especially some dinoflagellate species, are bioluminescent, which means that they can glow due to chemical reactions inside their cells. This glowing light is often blue and appears when the plankton are disturbed by waves, currents, or even footsteps along the beach.

Bioluminescence is thought to be a defence mechanism, startling predators or making plankton harder to detect. These glowing organisms are particularly common in warm coastal waters, and spectacular light displays can be seen in places such as the Maldives, Puerto Rico, and even along parts of the Cornish coast.

Dive Deeper: Marine Biogeochemistry

Marine Biogeochemistry is the incredibly complex web of biological, chemical, and physical processes that happen throughout our seas, with a special focus on how essential elements like carbon and nutrients cycle through living things.

These processes are happening everywhere, from the sunlit surface waters where tiny plankton bloom, to the darkest ocean trenches where unique bacteria have their own way of making a living.